Written by Nariste Alieva

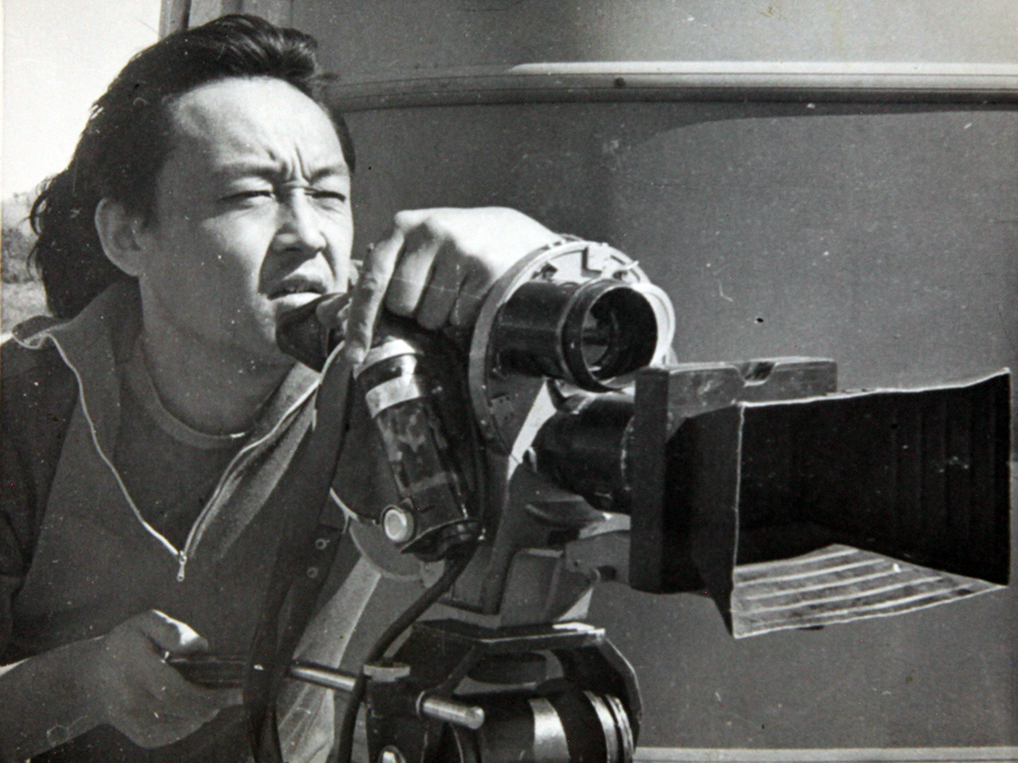

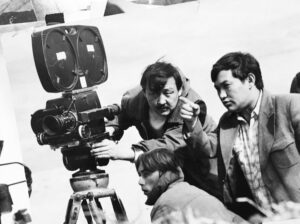

In the annals of the Kyrgyz and Central Asian cinematography, Murat Aliev stands as a luminary, a masterful weaver of visual narratives whose impact resonates across the decades of Soviet legacies, post-Soviet transitions, and the contemporary landscapes of Kyrgyz and Central Asian cinema. As a cinematographer, director of photography, and the Honored Worker of Kyrgyzstan, laureate of the State Prize of the Kyrgyz SSR, and member of the Asia-Pacific Film Academy, Murat Aliev has left a deep and memorable mark both in the history of Kyrgyz cinema and in the history of cinema throughout Central Asia.

This article unearths Aliev’s avant-garde visual narratives, spotlighting his groundbreaking portrayal of women. A meticulous dissection of his craft uncovers the magic in his framing, composition, camera fluidity, and the interplay of light and shadow, shaping the enduring impact of his artistry. Delving into acclaimed works such as “Spring Rainbow”, “Kurmanjan Datka,” “Kelin,” and “Snipers,” this journey illuminates Aliev’s indelible mark on cinematography, unveiling the maestro’s mastery of visual storytelling and technical finesse.

Aliev’s filmography reads like a cinematic odyssey, navigating the tumultuous waters of the Soviet Union’s decline, the birth of independent Kyrgyzstan, and the complexities of the modern era. From the sweeping landscapes of «The Great Silk Road» (1991) to the poignant tales of «Mustafa Shokai» (2007), Aliev’s lens mirrors the historical arc of Central Asian nations. Each film becomes a time capsule, preserving not only narratives but the very essence of the cultural and societal changes echoing through time.

The accolades bestowed upon Murat Aliev stand as testaments to his brilliance in the world of cinematography. «Kurmanjan Datka» not only claimed the Best Film title at the Tiburon International Film Festival (IFF, California, USA), but also earned Aliev the honor of Best Cinematography. “Through the eyes of the ghost” directed by Rustam Ibragimbekov, this film was awarded with the “Nika” award for the best film in the CIS countries and “Kelin” directed by Ermek Tursunov, winning the Best Cinematography at the New York Eurasian Film Festival.

Film «Shal» has brought Murat Aliev the Film Achievement Award in Asia Pacific for Best Cinematography at the Asia Pacific Screen Awards. These awards not only celebrate Aliev’s talent but also elevate Kyrgyz and Central Asian cinema onto the global stage.

Murat Aliev has filmed over 45 feature films and documentaries. His films: «Kurmanjan Datka» (2014), «Zhat» (2015), «Shal» (2012), «Through the Eyes of a Ghost» (2009), «Kelin» (2008), «Mustafa Shokai» (2007), «Cloud» (2003), «The Great Silk Road»(1991), «Ascent to Fujiyama» (1989), «Snipers» (1985), «The First» (1984), «Spring Rainbow» (1979), «Among People» (1978) and many others represent the development of cinematography through the era of the decline of the Soviet Union, the post-Soviet period of formation independent Kyrgyzstan and the modern era.

Visual Mastery of Murat Aliev

From the first flicker of light on a screen, cinema has captivated audiences with its ability to transport them to different worlds. However, behind every captivating image on the big screen are skilled artists who bring it to life. From film producer to director, sound maker, script writer and actors, it takes a whole team of devoted craftsmen to make a film. But honestly, the truth is that we see cinema through the eyes of a cinematographer: the whole essence of cinema is revealed by a wide palette in the hands of a skilled master cinematographer – director of photography (DP). The director of photography, also known as the cinematographer, is responsible for capturing the visual essence of a film. Cinematographer works closely with the film director to create a specific look and feel for each scene, using lighting, camera angles, and composition to convey emotion and meaning. DPs give their absolute best in technical and artistic craft by changing lights and shadows, concluding what ought to be behind the scenes and what ought to be engaged, and picking the right camera angle and composition. From the opening shot to the final frame, cinema is a visual medium that relies on the artistry of the director of photography. Their work is not just technical, but an art form that requires a deep understanding of storytelling and visual language.

Through the use of lighting, camera angles, and composition, the director of photography creates a specific look and feel for each scene, conveying emotion and meaning to the audience. In film, every visual element, from the color palette to the placement of objects in a shot, carries meaning and contributes to the overall message of the film. The director of photography plays a crucial role in interpreting and communicating these visual cues to the audience. And the last, but not the least, the craft of the director of photography is not only of the technical premise, but of the high artistic demise. One man who has crafted his art of cinematography perfectly is Murat Aliev. In the realm of filmmaking, where every frame is a canvas, Murat Aliev emerges as a masterful artist, whose lens has etched its mark on the tapestry of Kyrgyz and Central Asian cinema.

Aliev’s contribution to the development and artistic enrichment of the national Kyrgyz cinema is significantly undeniable. Being a bright representative of the glorious galaxy of cinematographers of the 20th and 21st century, he inscribed his name in the history of Soviet, Kyrgyz, Kazakh and Azerbaijani cinematographers.

Aliev’s works are characterized by conciseness and scrupulous thoughtfulness of the pictorial solution. As a skillful cinematographer Aliev uses a range of techniques from camera movements and angles, “mise en scène,” and balance of light and shadows to fully display a variety of emotions in his shots.

At the heart of Aliev’s craft lies an arsenal of visual techniques meticulously employed to evoke emotion, specific atmosphere and narrative depth. His works exemplify a conciseness and scrupulous thoughtfulness in the pictorial solution. Through camera movements, he orchestrates a dance of perspectives, immersing the audience in a dynamic visual journey. Whether it’s the picturesque fluidity of «Kurmanjan Datka» (2014) or the carefully crafted scenes in «Shal» (2012), Aliev’s skillful use of angles, mise en scène, and the interplay of light and shadows breathe life into his frames.

Beyond the technical virtuosity lies Aliev’s unique ability to capture the human experience through visual storytelling. His films, such as «Through the Eyes of a Ghost» (2009) and «Kelin» (2008), transcend cultural boundaries, resonating with audiences across the CIS countries and beyond.

Aliev’s contributions have transcended mere filmmaking, embodying a nuanced understanding of visual language that encapsulates the evolution of cinema through shifting epochs: from Soviet and Post Soviet to Modern Eras of cinematography of Kyrgyzstan and Central Asia.

An in-depth analysis of his artistic techniques unveils the enchantment woven into his use of framing, composition, camera movement, and the interplay of light and shadow, all contributing to the lasting influence of his creativity. As we delve into renowned pieces like «Spring Rainbow,» «Kurmanjan Datka,» «Kelin,» and «Snipers,» this exploration sheds light on Aliev’s profound impact on cinematography, showcasing his adeptness in visual storytelling and technical prowess.

Youthful Echoes of the Past: Murat Aliev’s Cinematic Poetry in «Spring Rainbow»

Murat Aliev was born on 10 December 1948 in the city of Naryn. He started his career in 1966 at the Kyrgyzfilm film studio as an assistant cameraman. He worked with well-known Kyrgyz operators Marles Turatbekov, Kadyrzhan Kydyraliev, and Nurtai Borbiev.

In 1979, he graduated from VGIK’s cinematography department. In the 80th-90th, he worked at the Kyrgyzfilm studio as a cinematographer-director of the films: The First directed by Gennady Bazarov, Snipers, and Ascent to Fuji directed by Bolot Shamshiev, The Great Silk Road directed by Karidin Akmataliev. During this period, Murat Aliev made more than 30 chronicle-documentaries as a director-operator.

Aliev’s cinematic journey unfolded during the vibrant decades of the 70s and 80s, a period marked by “Thaw” era in the Soviet Union, effervescence of youth and the urban transformation of the Frunze city with pulsating and youthful energy of the 1970s. It was an era characterized by the active construction of cities, a visual symphony of architectural evolution that mirrored the changing aspirations of the society. The peculiarities of 1970s architecture, with its consideration for natural spaces and historical resonance, found expression in Aliev’s lens. During this time he has filmed one of the most reminiscent movies of the “Thaw” era – films “The First” and “Spring Rainbow”.

Murat Aliev’s Cinematic Poetry in “Spring Rainbow”

Murat Aliev’s Cinematic Poetry in “Spring Rainbow”

In the annals of the Soviet Kyrgyz cinema “Spring Rainbow” (1979), directed by filmmaker Karedin Akmataliev, stands as a testament to Murat Aliev’s masterful cinematography, weaving a visual tapestry that captures the essence of a transformative “Thaw” era, offering a visual feast of lightness, reverence towards people, and an infectious enthusiasm that mirrored the new ideals of the 70’s.

The “Thaw” era in the Soviet Union was a period of cultural and political thawing, marked by a more open, optimistic, yet patriotically charged youth culture. The film, set against the backdrop of the Soviet Union’s ideological shift, captures the essence of an era through Aliev’s poetic lens. The cityscape, frozen in time, serves as a silent witness to the ebb and flow of societal tides. Aliev’s cinematography breathes life into Soviet urbanism, and as we traverse its streets, we become time travelers, navigating the echoes of the past.

The very title of the film «Spring Rainbow» speaks of the onset of a «thaw» – a kind of breath of fresh air of freedom and joy in the societal and cultural landscape of the Soviet Union. The film “Spring Rainbow” delicately explores the themes of youth, duty, decency, truth, dignity and Soviet idealism, painting a vivid portrait of a society caught in the winds of positive change. The film’s title serves as a metaphor for the societal and cultural “Thaw” that swept through the Soviet Union and Soviet Kyrgyzstan (Soviet Kirghizia). Here in this film Aliev’s lens becomes a prism through which the film not only documents the physical changes in the city but also encapsulates the emotional and ideological shifts marking the intangible spirit of a generation caught between the echoes of tradition and the promises of a burgeoning future.

In «Spring Rainbow,» viewers witness the foundation of the modern Soviet Kirghizia with its central architectural structure of the Frunze city — the Philharmonic Hall. Murat Aliev’s camera doesn’t merely document construction; it immortalizes the spirit of progress and naive optimism of youth mirroring the architectural changes of the “Thaw” era, capturing the construction boom of the 1970’s, symbolizing a final departure from nomadic structures of the past.

Poetic cinematography of Murat Aliev

In the delicate dance between light and shadow, where the cityscape meets the lens of Murat Aliev, a visual poem unfolds. His lens, a brush, paints the canvas of the film «Spring Rainbow» with the delicate hues of hope, nostalgia, and the timeless pursuit of ideals. As we revisit this cinematic masterpiece, we are not mere spectators but active participants in a journey through the alleys of memory.

Through the lens of Aliyev, the cityscape becomes a visual poem, and the ideals of youth resonate across the decades. As we revisit «Spring Rainbow,» we are not just witnesses to the past but participants in a journey painted with the vibrant strokes of light, hope, and the enduring pursuit of ideals. Cultural liberation is painted with poetic cinematography of Murat Aliev documenting the blossoming of artistic expression of the youth, showcasing vibrant streets of the city, open-air gatherings in the parks, a newfound openness in public spaces filled with fresh beauty of the urban landscapes.

«Spring Rainbow» stands as a testament to Aliev’s mastery in transforming the ordinary into the extraordinary. The city, often dismissed as a mere backdrop, becomes a character in its own right. Each frame is an ode to the urban landscape, a lyrical exploration of architecture and humanity coexisting in a delicate dance.

What sets Aliev apart is his ability to infuse the frames with delicate emotions. His lens is not just a mechanical device capturing scenes but a storyteller, weaving narratives through the play of light and the careful composition of each shot. The camera becomes an extension of his soul, translating the intangible essence of emotion onto the screen.

As we delve into the thematic layers of «Spring Rainbow,» Aliev’s lens becomes a prism refracting the ideals of youth. The film becomes a mirror reflecting the universal quest for a brighter tomorrow, a rainbow emerging after the storm. The city, with its architectural tapestry, becomes a metaphor for the dreams woven by the youth – intricate, complex, and evolving.

In the film “Spring Rainbow” special techniques are used to make the audience feel as observers. Aliev moves the camera a lot in a discrete yet noticeable voyeuristic presence, as if the viewer is following Ormon, the main protagonist, stealing the glance at the characters as if everything is happening here and now, elevating the camera to the status of a silent, discerning character.

Student Ormon is not merely a character; he is a vessel through which Aliev navigates the complex emotional landscape of the “Thaw” era. The camera, in sync with Ormon’s journey, captures the subtleties of light and shadow that play across his face, embodying the nuances of his deeply poetic and at times naive character.

The play of light in «Spring Rainbow» is also a character in itself, dancing through the lens with the grace of a ballet dancer echoing the melancholy and delicate dancing of the female character of the film. Aliev’s meticulous framing captures the interplay between sunlight and shadows, casting a spell that transcends the screen.

«Spring Rainbow» is a canvas on which Aliev paints with shadows and light, weaving a narrative that goes beyond words. The camera, imbued with a voyeuristic grace, invites the audience to not merely watch but immerse themselves in the story. It becomes an accomplice, a silent confidant to the characters’ dreams, struggles, and triumphs.

“The Great Silk Road”: Murat Aliev’s Documentary Visual Pilgrimage through Time and Culture

In the realm of Kyrgyz cinema, “The Great Silk Road” emerges as a groundbreaking masterpiece under the artistry of film director Karedin Akmataliev and profound cinematography of Murat Aliev. This film not only breaks new ground in Kyrgyzstan’s cinematic landscape but also transcends borders and epochs, offering viewers an in-depth historical, cultural and spiritual pilgrimage through countries and centuries.

“The Great Silk Road» stands as a unique documentary in the history of Kyrgyz cinema, venturing beyond traditional storytelling to create a real-time historical, cultural and spiritual odyssey to the origins – monuments of ancient civilizations from Mesopotamia, Ancient Rome, Central Asia and Tokyo. Here in this film, Murat Aliev’s lens is a meticulous chronicler of the rich tapestry woven by the Great Silk Road, transforming the 13 parts of the film into a cinematic collection, an encyclopedic journey that narrates the treasures and tales of the Great Silk Road.

«The Great Silk Road» was filmed in 1991 at the Kyrgyzfilm film studio with the assistance of the USSR State Cinema, as well as the Japanese film company Asahi Shimbun. The film is a realtime testament to the encyclopedic accuracy achieved through Aliev’s dedication to capturing the invaluable museum exhibits, vibrant modern life of urban capitals and capturing the vast impressiveness of the landscapes. Every frame becomes a page of a visual encyclopedia, a testament to the detailed study of the Central Asian route, following the director’s script and the insightful commentary from knowledgeable scientific contributors.

One of the Aliev’s cinematic triumphs in “The Great Silk Road” lies in his ability to capture the breathtaking landscapes of Eurasia. From the rolling desserts to the towering mountain ranges with the endless caravans, every scene unfolds like a painting, showcasing the diverse and awe-inspiring beauty that once served as the backdrop for the historical trade routes.

Aliev’s lens doesn’t merely linger in the past; it also paints a vivid portrait of the modern world along the Silk Road; juxtaposition of ancient relics against the bustling life of contemporary cities adds a dynamic layer to the film. Viewers are transported not only through time but also across the evolving landscapes of the end of the 20th century.

Ekaterina Luzanova’s words ring through: «Cinematographer Murat Aliev captured the impressive landscapes of Eurasia, the most valuable exhibits of museums, and the modern life of millennial capitals. High reliability is provided to the film by a detailed study of the route, the director’s script, and the participation of competent interlocutors.»

Extensively expressive canvas of Murat Aliev in the “Ascent to Fujiyama”

In the vast expanse of cinematography, there are films that transcend time, awaiting rediscovery by a new generation of moviegoers. One such hidden gem is «Ascent to Fujiyama,» a poignant and dramatic masterpiece that remains overlooked in the contemporary cinematic landscape. This article aims to shed light on the cinematic brilliance of Murat Aliev as the director of photography for this timeless masterpiece.

«Ascent to Fujiyama» is a testament to the enduring power of storytelling – despite the passage of time, the narrative of «Ascent to Fujiyama» remains as relevant and impactful as ever. Created in 1973 by film director Bolotbek Shamshiev in collaboration with genius Kyrgyz writer Chingiz Aitmatov together with Kazakh author Kaltai Mukhamedzhanov, the film explores universal themes, weaving a rich tapestry of human relationships, ever-present quest for friendship and betrayal, good and evil, freedom and totalitarian power. Even today, those who have had the privilege of watching this cinematic masterpiece attest to its timeless resonance.

The film tells the story of friendship and betrayal in the Soviet era. Four former friends Mambet, Dosbergen, Joseph and Isabek, together with their wives and an old teacher Aisha Apa, gathered to celebrate the May holidays on Mount Karaulnaya. Friends jokingly call this mountain Fujiyama because of its highness and “proximity to God”, therefore, once the four friends arrived at the top of the mountain, they agreed to speak the truth and be open and honest in conversation.

Once four of them had a fifth friend, Sabyr, now absent, with whom they studied at school together. Sabyr went to the front and fought. Physically, he is not with them at Fujiyama, but he is still invisibly present among them – each of the friends has an echoing memory: Sabyr wrote a poem at the front that did not correspond to the canons of the official ideology. One of his friends betrayed him by writing a letter of denunciation. The talented poet was sent to jail. He was rehabilitated later. But after a friend’s betrayal, Sabyr turned into an alcoholic, and then disappeared into obscurity. The memory of the betrayal is echoing with pulsating drama. The feast soon turns into a drunken revelry. The evil committed many years ago leads to new evil and human casualties…

In an era marked by globalization and the blending of diverse cultures, the themes explored in the «Ascent to Fujiyama» take on renewed significance. As we navigate the complexities of the modern world, the themes explored in “Ascent to Fujiyama” serve as a poignant reminder of our shared humanity, making the film not only a product of its time but a timeless exploration of the human condition.

It is high time for “Ascent to Fujiyama” to reclaim its place in the spotlight, allowing its visual poetry to resonate with audiences anew. Murat Aliev’s contribution as the director of photography for “Ascent to Fujiyama” deserves double recognition and rediscovery. Here, in this masterpiece, Aliev goes beyond capturing images; he crafts an immersive experience that resonates with the audience on a profound dramatic level. His lens transforms the screen into a canvas, each frame a brushstroke that delicately paints the intense emotional landscape of the narrative.

“Capturing the Power of Women in Film: Murat Aliev’s Cinematic Reverie on Women”

In the realm of cinematography, few wield the camera as a brush on the canvas of storytelling with the finesse that Murat Aliev brings to his craft. However, what distinguishes Aliev from his peers is not only his artistic and technical prowess but also his ability to transcend the conventional portrayal of women in historical and artistic narratives. Through his cinematic craftsmanship in films like «Kurmanjan Datka,» «Snipers,» and «Kelin,» Aliev transforms the representation of women, elevating them to powerful emblems of female leadership in patriarchal societies.

Murat Aliev’s lens has a magical quality, an alchemy that transforms the portrayal of women from the two-dimensional figures often seen in historical narratives to complex multidimensional, nuanced characters. His cinematic craftsmanship not only captures the external beauty but delves into the inner complexities, emotions, rivalry, leadership and struggles that define these women.

Murat Aliev’s cinematography in «Kurmanjan Datka» is nothing short of a cinematic revolution in Kyrgyz contemporary portrayal of women. By magnifying the strength and resilience of Kurmanjan, he not only immortalizes her story but also becomes a pioneer in feminist cinematography. As we revisit this cinematic gem, we celebrate Aliev’s ability to break the chains of traditional portrayals and offer a nuanced, empowering lens on historical narratives, proving that the stories of women, even in patriarchal landscapes, deserve to be told with authenticity, respect, and a feminist perspective.

Kurmanjan Datka: A Symphony of Bold Female Leadership

One of the striking examples of Aliev’s prowess in portraying women is evident in his work on «Kurmanjan Datka.» In this historical epic, Aliev’s lens becomes a storyteller, capturing the essence of a remarkable female leader in Central Asian history. Kurmanjan Datka, played by Elina Abai Kyzy, is not merely a character on the screen but a force of nature. Aliev’s lens delves into the complexities of her character, portraying the strength etched on her face and the fire in her eyes that mirrors the indomitable spirit of a leader in a patriarchal society.

In the tapestry of cinematic history, certain films stand as beacons of empowerment, challenging societal norms and spotlighting untold narratives. «Kurmanjan Datka,» brilliantly captured through the lens of director of photography Murat Aliev, is one such cinematic jewel.

The film is not a static historical reenactment; it is a dynamic exploration of Kurmanjan Datka’s internal world—her struggles, victories, and the sacrifices she makes for her people. Aliev’s lens serves as a conduit, translating the silent strength of Kurmanjan Datka into a visual symphony that resonates with audiences on a profound level.

Directed by Sadiq Sher-Niyaz, this film not only captures the tumultuous historical events of the 19th century but also becomes a canvas for the powerful portrayal of a woman leader and ruler, Kurmanjan Datka. Murat Aliev’s director of photography work in this film is nothing short of revolutionary, creating a feminist lens that illuminates Kurmanjan’s journey with picturesque precision. This article delves into Aliev’s picturesque and powerful portrayal of the woman leader and ruler, Kurmanjan Datka, a narrative that serves as a revolutionary benchmark in the realm of feminist cinematography.

A Feminist Lens on Kurmanjan Datka

In the world of Kurmanjan Datka, Murat Aliev’s lens transcends the conventional portrayal of women in historical narratives. His cinematic craftsmanship enriches the character of Kurmanjan, turning her into more than just a historical figure but a powerful emblem of female leadership in a patriarchal society. One of the film’s pivotal scenes captures the essence of Kurmanjan’s struggle against patriarchal norms.

Powerful Mise-en-Scene: Communication With Men as an Act of Balance and Power

A pivotal mise-en-scène in «Kurmanjan Datka» unfolds when Kurmanjan receives a symbolic will from her husband Alymbek—to unite the Kyrgyz people. In a powerful portrayal of leadership, Kurmanjan confronts internal strife within her tribe, where men contemplate surrendering to Kokand troops. Aliev’s lens captures her emergence as a strategic ruler and fighter, attired in dark gray chapan, symbolizing a departure from traditional female roles. The absence of black, typically associated with widowhood, instead emphasizes her rising strength.

Kurmanjan’s attire becomes a symbol of her resilience and transformation. The silver gray head-dress reflects her steel-like strength, challenging gender norms. The dark gray chapan, a patriarchal attribute, signifies her embrace of manly features. Aliev’s choice of symbolism transcends the screen, portraying Kurmanjan as a warrior woman who communicates with men in their language, respecting patriarchy to inspire unity.

Kurmanjan’s attitude towards men in this scene is both powerful and subtle. While expressing her disappointment in their cowardice, she refrains from blame, opting for wisdom. Her words resonate with the essence of feminism as she prioritizes the collective interest over individual grievances. The semiotic language intensifies as the camera captures Kurmanjan against the backdrop of a blue sky and gray clouds, portraying her as a hero and ruler.

Warrior Women Spirit of Historical Significance

Kurmanjan’s dialogue encapsulates the warrior women spirit of the Kyrgyz, challenging the stereotype of women as mere caretakers. She declares solidarity with the men, emphasizing that they will face the enemy together. Aliev’s cinematography elevates this moment, portraying Kurmanjan as a hero through a low-angle shot, surrounded by the vastness of the sky.

In the tumult of political unrest, Kurmanjan’s astuteness earned her the title of Datka, a rare honor for a woman. Aliev captures her journey from widowhood to a political pragmatist who navigates political intrigues with intuition and everyday wisdom. The film pays homage to Kurmanjan Datka’s historical significance, being the only woman to receive a solemn reception at the palace of the Emir of Bukhara.

Thus, Murat Aliev’s cinematography in «Kurmanjan Datka» not only immerses the audience in the historical tapestry of Central Asia but also becomes a testament to the cinematic celebration of female leadership. In capturing Kurmanjan’s resilience, strength, and political acumen, Aliev pioneers a feminist lens that challenges stereotypes and creates a nuanced portrayal of women in positions of power. «Kurmanjan Datka» stands not just as a historical epic but as a cinematic triumph that reshapes our understanding of leadership and the indomitable spirit of women in history.

Snipers: The Power of Women at War

In the history of war cinema, certain films stand as vivid portraits of the indomitable human spirit amid the brutality of conflict. «Snipers» (1985) directed by Bolot Shamshiev and lensed by artcraft cinematography of Murat Aliev, is a harrowing journey into the heart of World War II, plunging audiences into the unforgiving crucible of 1943.

The cinematic narrative of «Snipers» unfolds at a pivotal moment in World War II, thrusting spectators into the midst of a turning point in 1943, showcasing the role of women in the front line of World War II.

At the heart of the narrative of the film “Snipers” is Aliya Moldagulova, a young, 18 years old sniper whose remarkable story unfolds from August 1943 to January 1944. During this short but impactful span, she notched an astonishing 78 kills, earning her the title of Hero of the Soviet Union posthumously. The film becomes a poignant exploration of the sacrifices made by individuals barely out of adolescence, thrust into the crucible of war and shaped by its unforgiving demands.

The Art of Realism and Immersion of the “Snipers”

Murat Aliev’s cinematography brings the art of the sniper into sharp focus, transcending the limitations of its era. Aliev’s lens immerses viewers in the harshness of war, following a recruitment drive that brings young girls, graduates of shooting courses, to the front lines. From the trenches to the front line, the film documents their training, courage, and inevitable confrontation with death. While the film may lack the technological sophistication of modern productions, its depiction of the sniper’s craft is nonetheless riveting.

“Snipers” film is a masterclass in immersion and realism. From the offensive battles to the intricacies of disguising terrain and tracking enemy movements, «Snipers» showcases the tactical brilliance and sheer audacity of these war heroes.

The film takes the audience behind the scenes of sniper warfare, unraveling the intricacies of the «profession.» It delves into the subtle yet critical elements, such as disguising the landscape, tracking the movements of the enemy, and the lessons imparted by seasoned warriors like Uncle Stepan. These nuances, brought to life by Aliev’s lens, elevate «Snipers» beyond a mere war film and into a compelling exploration of the psychological and strategic dimensions of the battlefield. Through striking cinema desaturation, handled cameras and low-angled shots Murat Aliev transforms the narrative into a here and now immersive reality presence. One of the most notable techniques that Aliev used in “Snipers” is the handheld camera. This technique gives the film a documentary-like feel and makes the viewer feel as though they are in the middle of the action. The handheld camera is used throughout the film, but it is particularly effective in the film’s opening sequence and closing scenes.

Murat Aliev’s director of photography work on «Snipers» stands as a testament to his ability to capture not only the visual spectacle of war but also the human stories that unfold amidst the chaos. The film, though potentially unfamiliar to contemporary audiences, remains a gripping cinematic journey into the grit and valor of those who faced the brutality of war. As we revisit this classic, we acknowledge the timeless relevance of its narrative and the enduring impact of Aliev’s cinematographic mastery in preserving the legacy of the sniper’s art.

In “Snipers” Aliev’s lens doesn’t just capture the physicality and brutality of war but delves into the resilience and courage of women who defied societal norms to defend their homeland.

The art of the sniper, as depicted by Aliev, goes beyond the tactical maneuvers; it becomes a symbol of empowerment. Through meticulous framing and evocative lighting, he transforms the battlefield into a stage where women emerge not just as soldiers, heroines challenging the gender norms of their time.

Kelin: A Matriarchal Parable and Murat Aliev’s Cinematic Eulogy to Matriarchy

In the haunting landscapes of «Kelin,» the absence of words becomes a canvas for Murat Aliev’s visual poetry, capturing the raw essence of prehistoric survival in the III-IV centuries AD. Directed by Ermek Tursunov, this cinematic parable masterpiece delves into a world devoid of civilized morality, where the primal laws of survival govern every human action. Aliev’s cinematography, a silent symphony of expressions, gestures, and movements, is an ode to the matriarchal spirit embedded in the characters of Kelin and Ene.

A Cinematic Silence

«Kelin» defies the conventions of dialogue, presenting a unique cinematic experience where characters communicate through non-verbal cues. Aliev’s lens becomes the narrator, capturing the intricate dance of emotions, passions, and primal instincts. This silence is not an absence but a powerful tool, giving voice to the unspoken narratives of two women who become symbols of procreation, continuity, and the preservation of life.

The Feminine Archetypes

At the heart of «Kelin» are two women, Kelin and Ene, representing distinct feminine archetypes. Kelin, portrayed as a symbol of youth, beauty, and passion, embodies the archetype of Aphrodite. Aliev’s cinematography accentuates Kelin’s sensuality, weaving the drama around her relationships with two husbands and a lover. The visual narrative becomes a poignant exploration of the complexities of desire and societal expectations.

Ene: The Hearthkeeper and Matriarch

Contrasting Kelin is Ene, the embodiment of the Hestia archetype. Wise, loyal, and mystical, Ene serves as the keeper of the household and ancient traditions. Aliev’s lens reveals Ene’s multifaceted role as the guardian of shamanic rituals, weddings, burials, and childbirth. Her wisdom is grounded in ancient traditions, and her actions are imbued with spirituality. The silence amplifies the power of Ene’s character, depicting her as a self-sufficient hearthkeeper passing the reins of the household to the next generation—personified by Kelin.

The Matriarchal Narrative and Archetypal Symbolism

«Kelin» takes an almost feminist angle, unraveling a matriarchal story where women emerge as the central figures. Through Aliev’s cinematography, the narrative challenges traditional gender roles, offering a nuanced exploration of femininity and strength, where men are considered to be just a biological tool for life to continue on and on. Kelin’s passionate desires and Ene’s wise stewardship create a harmonious balance, each representing the dualities of womanhood.

The archetypal symbolism embedded in the film is a testament to Aliev’s ability to infuse visual narratives with profound meaning. Kelin and Ene become more than characters—they embody universal archetypes, portraying the eternal dance between youth and wisdom, desire and responsibility, passion and spirituality.

«Kelin,» through the lens of Murat Aliev, emerges as a silent symphony, celebrating the feminine in its myriad forms. In a cinematic realm where silence speaks louder than words, Aliev’s visual storytelling becomes a testament to the resilience and complexity of women in a world governed by primal instincts. «Kelin» not only challenges cinematic norms but also becomes a timeless exploration of the feminine spirit, inviting audiences to witness the silent, powerful narratives woven through the tapestry of prehistoric survival.

Aliev’s commitment to portraying women as more than passive figures extends to «Kelin,» where the lens becomes a storyteller, weaving a parable about the prehistoric matriarchal era. In «Kelin,» Aliev doesn’t just capture the physical beauty of the female characters; he encapsulates their strength, wisdom, and the delicate balance between youthful passion and maternal grace.

Aliev’s lens, therefore, serves as a bridge between the historical context and the contemporary understanding of femininity, unfolding the rich tapestry of female leadership, resilience, and grace. It reframes the narrative, allowing women to step out of the shadows of history and take center stage. Through his artistry, Aliev empowers his female characters, making them not just subjects of the frame but active participants in the unfolding narrative.